Joshua Teoh explains how a decision of the Federal Court of Australia may be relevant to Malaysian patentees.

—

This article was first published in Issue 2/2018 of Legal Insights, a Skrine Newsletter. Reproduced with permission of Skrine.

In Sandvik Intellectual Property AB v Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 138, the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia affirmed the decision of Justice Jessup sitting as a single judge in the Federal Court of Australia, holding that the claims in Australian Patent No. 744870 entitled “Extension Drilling System” (“‘870 Patent”) belonging to the Appellant (“Sandvik”) were invalid for, among others, failure to comply with the requirement to describe the best known method of performing or carrying out an invention.

The aforesaid requirement is set out in section 40(2)(aa) of Australia’s Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“section 40(2)(aa)”) which stipulates that “a complete specification must disclose the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention”.

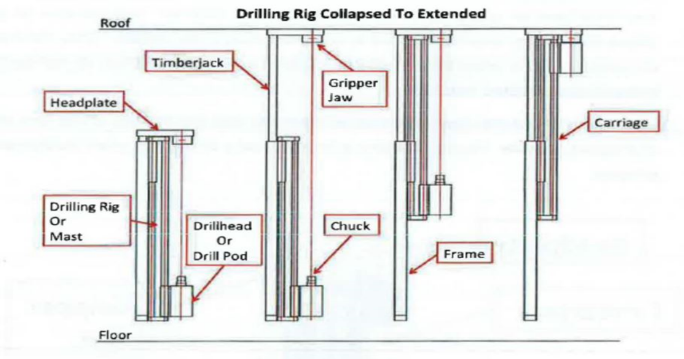

The technology in this case concerned an extension drilling system for drilling holes in subterranean mining operations such as coal mining, where the structure of the roof of a tunnel is to be rendered more secure by the insertion of rock bolts into the holes drilled into the roof structure. An illustration of a drilling system (drilling rig without drill rods connected at the chuck) is represented in the diagram below.

THE ‘870 PATENT

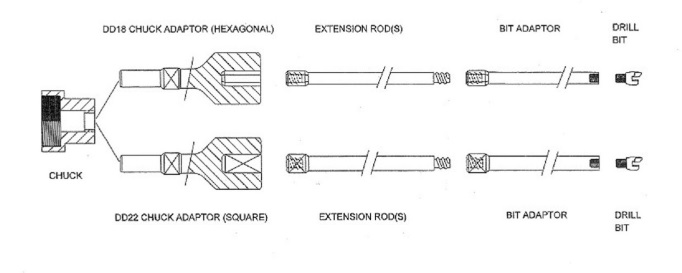

The ‘870 Patent claimed an invention over an extension drilling system. In the invention, each extension rod has a male right-hand rope-threaded connection at one end and a female right-hand rope-threaded connection at the other end. The extension rods are connected together by coupling the male end to the female end, and where a drive chuck (or an adaptor) drives the outside surface of the female end of the rod at the bottom end of the drill rod string such that during the process of uncoupling the drill rod string, there is only one threaded connection between the gripper jaws and the drive chuck (or adaptor). The following diagram illustrates the extension drilling system contemplated in the invention of the ‘870 Patent:

There were two preferred embodiments described in the specification of the ‘870 Patent (see diagrams below), where:

(a) The first preferred embodiment as depicted in Figures 1 and 2 show that the drill rods are directly connected to the drive chuck;

(b) The second preferred embodiment depicted in Figures 3, 4, and 5 involve the use of an adaptor. Figure 3 identified an alternative adaptor (referred to as a “direct drive chuck”) to the drill rods in Figures 4 and 5.

The ‘870 Patent described an axial passage within the connected drill rods, through which flushing fluid is pumped to the drill bit to clear debris from the drilling process and prevent the drilled hole from being clogged.

To inhibit the outflow of the flushing fluid when the lowest connecting rod is removed (and also to facilitate the insertion of the next rod), some or all of the drill rods are internally equipped with a non-return ball-valve arrangement. Further, at the end of the drill string, there is also a sealing member or water seal at the point where the adaptor sits in the chuck.

AT FIRST INSTANCE

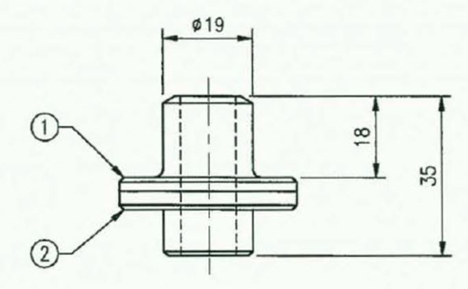

The Respondent, Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd, contended that the specification of the ‘870 Patent did not disclose the best method of performing the invention when it omitted to refer to the particular type of sealing member known to Sandvik at the date of filing. On this, the issue before the Federal Court was whether the specification disclosed by Sandvik included an upwardly-extending cylindrical part (marked red in the diagram below).

Justice Jessup held that:

(a) The specification of the ‘870 Patent did not disclose a sealing member with upper and lower sections – it only disclosed a horizontal sealing member;

(b) At the time of filing the complete specification, Sandvik had developed a sealing member with upper and lower sections, which was an improvement on a purely horizontal sealing member;

(c) Even though it was not part of the invention claimed, Sandvik ought to have disclosed in the specification the improved sealing member with the extended parts, as depicted below:

THE APPEAL

The Full Federal Court observed that the purpose of the requirement in section 40(2)(aa) to disclose the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention is to allow the public the full benefit of the invention before the patentee’s monopoly expired. Although a patentee might not be explicitly required to act in good faith, the principles of good faith underlie the best method requirement, to protect the public against a patentee who deliberately keeps to himself something which he knows gives the best results. The nature and extent of the disclosure required to satisfy the best method requirement will depend on the nature of the invention itself.

Section 40(2)(aa) is directed to the method of performance of the invention. Even though the monopoly is circumscribed by the claims, the nature of the invention is as described in the whole of the specification. The requirement to describe the best method of performing the invention is ordinarily satisfied by including in the specification a detailed description of one or more preferred embodiments of the invention.

The Full Federal Court set out the approach to determine whether the patentee has fulfilled the best method requirement:

(a) First, identify the invention described in the specification as a whole, as distinct from the invention as claimed in the claims.

(b) Second, determine whether the omitted part is necessary and important to perform the invention or otherwise carry out the invention. Even though the water seal was not part of the invention described in the specification, the use of an effective water seal was nevertheless necessary and important to perform the invention. There was evidence that designing an effective water seal was “a real and important issue which needed to be overcome”.

(c) Third, in circumstances where the specification purported to address the best method requirement, such as by providing a detailed description of two preferred embodiments and where one embodiment refers to a particular type of sealing member, it was incumbent on Sandvik to describe the best embodiment known to it.

In the above premises, the Full Federal Court affirmed the earlier finding that Sandvik did not disclose an important sealing member known to them and hence failed to provide the best method of performing the invention in the ‘870 Patent.

CONCLUSION

Although the Malaysian Patents Act 1983 has no provision identical to section 40(2)(aa), regulation 12(1)(e) of the Patents Regulations 1986 provides that the patent description shall “describe the best mode contemplated by the applicant for carrying out the invention, using examples where appropriate and referring to the drawings, if any”. Section 23 of the Malaysian Patents Act requires every application to comply with the prescribed regulations, and failure to comply renders a patent invalid pursuant to section 56(2).

While it remains to be seen if the Malaysian courts will impose similar obligations on applicants to disclose the best method or embodiment known to the applicant to carry out the invention, the Sandvik case is a cautionary tale that applicants should ensure that their patent specifications are complete and updated prior to filing. The specification should include the full details of the best method known to the applicant at the time of filing even though such details are not claimed as part of the invention but are nevertheless necessary and important to carry out the invention.

—

About the Author

Joshua Teoh graduated from the University of Malaya with a Bachelor of Laws degree in 2011. He commenced his pupillage in Skrine and later joined the firm as an Associate upon being admitted as an Advocate and Solicitor of the High Court of Malaya in July 2012. His main areas of practice are Intellectual Property Litigation, General Litigation, Shipping & Maritime and Public & Administrative Law.

Email: joshua.teoh@skrine.com